Riddle me this: why is it that when Serena Williams walks out onto a tennis court the entire world gives her their attention, but when this same woman is in a hospital complaining of difficulty breathing after giving birth, her complaints get waved off by the medical staff?

Why is it that Shamony Gibson, another Black mother, had to go through almost the exact same struggle with her own health care providers, delaying the care she received and ultimately resulting in her death?

Why is it that cases such as these are not uncommon in America, and why do they continue to happen?

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman from complications of pregnancy or childbirth that occur during the pregnancy or within six weeks after the pregnancy ends1.

Out of all the developed countries, the United States has the highest maternal mortality rate and it has been steadily increasing.

As of 2021, the average U.S maternal mortality rate was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, whereas in 2018 it was 17.4.

However, when looking at the statistics for African American mothers, the difference is drastic: 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births; over twice the national average, and the highest rate for any race by a significant margin2.

So once again, I urge you to ask “Why?”.

America’s dark past and the prejudice derived from it are correlated factors that have allowed the issue of Black maternal mortality to persist and putrefy to the point that it has. In order to better understand the status quo, it’s vital that we take a look at the origins of the problem along with everything that’s helped fuel it so that we can figure out how our country can move forward.

While the injustice of slavery and how its roots have shaped today’s culture is a well known matter, one facet of this topic that is less spoken about is its influence on how American healthcare treats African American mothers.

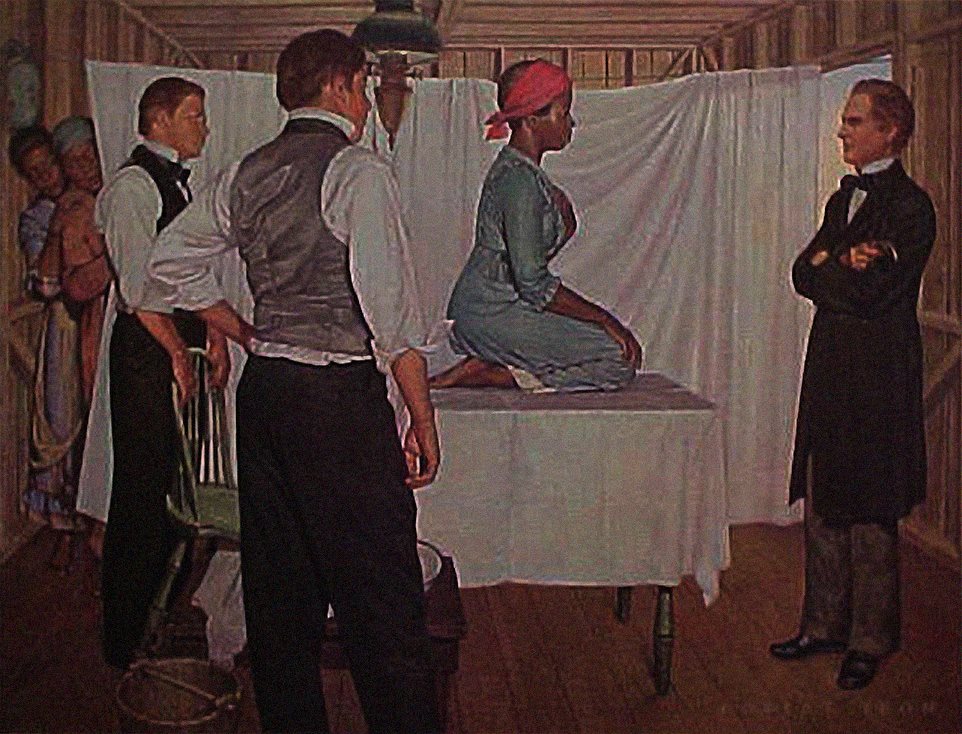

In that regard, I’d like to focus on one man: James Marion Sims, who has been given the title of “The Father of Modern Gynecology” for his work in developing surgical tools such as the modern speculum and surgical techniques for repairing a complication such as that of a vesicovaginal fistula (VVF)3.

Although his discoveries have undoubtedly proven beneficial for the field of medicine, his methods for producing those results were questionable to say the least.

Sims built a reputation for himself as someone whom wealthy plantation owners could rely upon to treat their slaves- this way, the slaves could get back to working condition and continue reproducing for their owners to keep their “value”.

It was from these same owners that Sims received a ready supply of subjects he used to come up with a way to fix a VVF.

The trials and procedures Sims performed on these women were long and painful, and although Sims’ autobiography states that the slaves he operated on wanted the procedure done themselves, the question of whether or not those women, who were considered “property”, had the option to say no remains4.

Aside from the problem of consent, there is also the theory that Sims believed that Black women experience pain differently than their white counterparts, and were therefore better suited to endure experiments such as the ones he performed.

The controversy of whether not Sim’s supported the idea of race dependent differences in pain tolerance persists, and while he never explicitly stated this belief, his used methods along with his credence that African Americans were less intelligent due to their skulls “growing too quickly” around their brain certainly reflects this notion5,6.

Regardless of whether or not he supported this theory, it is a known fact that other physicians of that era such as Dr. Thomas Hamilton did, which gives way to the point that I’m trying to make: the past has had a considerable influence on where we are in the present6.

Just think about it. Discoveries that served as pillars for what modern gynecology is were built off the fact that slave owners wanted what was most profitable for them: working slaves that were able to reproduce. Furthermore, while Sims’ findings and techniques were passed down in time, it is very well likely that his ideologies were as well, and the same can be said about the countless other doctors of that time who’d perform experiments on slaves.

The adverse effects of such fallacies being passed down can seen through a research study featuring two hundred-twenty-two white medical students and residents which found that “around half [of those surveyed] endorsed false beliefs in biological differences between blacks and whites”, including statements such as “black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people’s nerve endings” and “black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s skin”7. Furthermore, “those who [endorsed the false beliefs] also perceived blacks as feeling less pain than whites”, which made them more likely to insufficiently treat Black patients7,8.

The results from this study illustrate how pre existing biological fallacies have trickled down in time to establish implicit racial biases in medicine, and the consequence of such ignorance- intentional or not- is the suffering of Black patients across America.

One example of such partiality at play is how a meta-analysis of 20 years of studies showed that “black/African American patients were 22% less likely than white patients to receive any pain medication”9.

We can see an instance of a Black patients’ pain not being taken seriously from the example I gave in the beginning. When Serena Williams, someone with a known medical history of blood clots and pulmonary embolism- a complication that postpartum women are at higher risk for- began reporting symptoms of the condition after having an emergency C-section, a nurse told her that “the pain medication had perhaps left [her] confused”10.

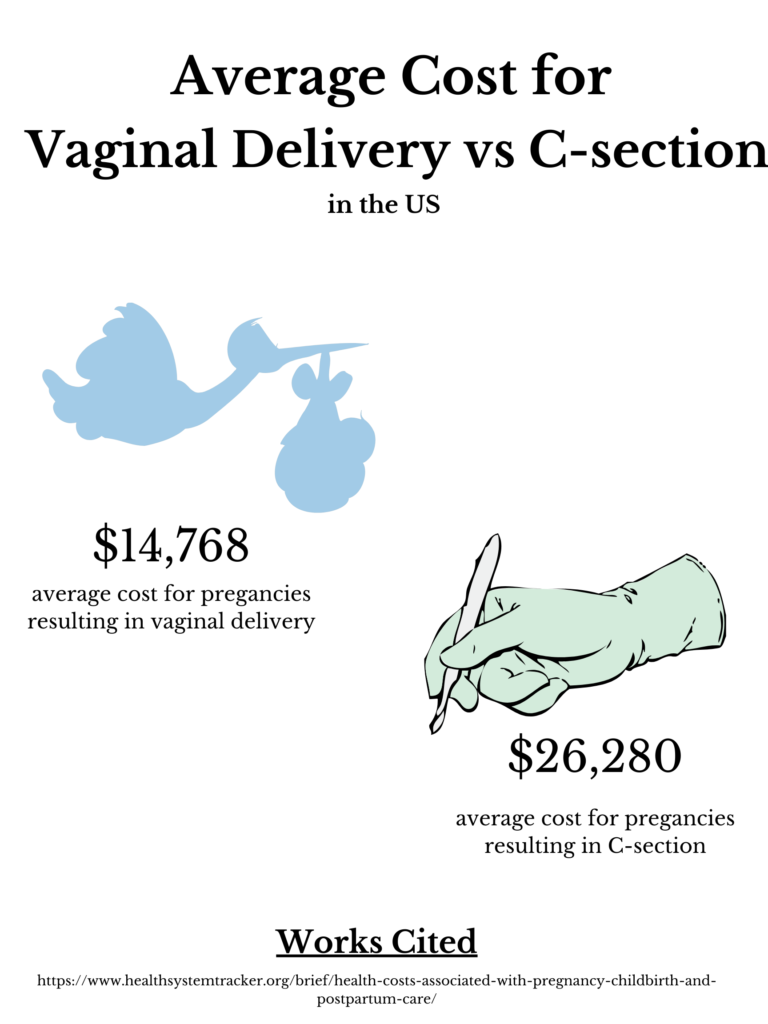

This reminds me of one more thing: the fact that Black women also have C-sections at a disproportionately higher rate than any other race, even in low-risk cases where it is not required.

C-sections are essential in circumstances where there is a problem with the progression of labor, the baby is in distress, or other kinds of health concerns, but they also have the downfall of increasing the risk of future pregnancies, infection for the mother, blood clots, etc., which is why they should be used only when neccessary11.

For first-time births, healthy Black women are 21% more likely to deliver via C-section than white women even when they’re at low risk, which shows that something isn’t adding up12.

Natural deliveries take longer than C-sections which is more costly for the hospital. C-sections, however, are not only significantly shorter, but also allow hospitals to charge a lot more, making them overall more profitable.

The fact that C-sections are more “beneficial” for the hospital to perform, paired with the poor patient-provider interactions many Black patients experience, along with the stress that comes during delivery can almost force an unwanted cesarean delivery onto the mother. Another possible reason is that providers can overestimate the risks of a vaginal birth in a black mother, leading them to a higher rate of C-section interventions.

This could create a nasty cycle where the complications following a C-section only go on to increase African-American maternal mortality and morbidity rates, which in turn leads to further harmful overtreatment.

There are no sole reasons that have been identified as causes for this trend, and the explanations I gave above are merely just educated theories for why it occurs; however, the numbers show that there is an undeniable problem in our hospitals and it must be further addressed.

It is absurd how even when you take into account differences in social class, marital status, and education, the treatment Black mothers receive at hospitals and their outcomes are far different from that of their white counterparts.

There are many reported cases of Black mothers’ being pressured into undergoing certain procedures, medical staff assuming they were on Medicaid because of their skin color, and suggesting they were seeking opioids when reporting pain. This further reiterates how racial bias causes mistrust between patients and healthcare workers, which only further impedes care.

Aside from what goes on in the hospital, there are also outside factors that can harm the wellbeing of Black mothers.

Limited access to prenatal care can adversely impact a pregnant woman and her fetus’ health, and because a lesser percentage of Black mothers participate in prenatal care from the first trimester than white and Asian mothers, this is also bound to be related towards the struggles they face13.

In addition, African Americans also have higher rates of pre-existing chronic health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, heart diseases, and other disorders. Such predispositions can affect the health of Black mothers during pregnancy, especially when adding how black women have shown to develop preeclampsia- a potentially dangerous complication of pregnancy caused by high blood pressure- at higher rates than their Hispanic and white counterparts.

What I find interesting about this is how foreign born non-hispanic Black women living in America have 27% lower odds of preeclampsia compared to US born non-hispanic Black women14. However, when looking at foreign born non-hispanic Black women who lived in America for 10 years or more, their odds of preeclampsia were higher than those who didn’t- a perfect example of the healthy immigrant effect.

So given the plethora of facts, statistics, and theories I’ve thrown at you up until now, where do we go from here? How do we go about fixing this?

It took years of indifference, ignorance, and the inability to recognize the issue for us to end up where we now stand, which means that it’s going to take just as long if not longer for us to make a world where Black mothers don’t face the fear of becoming a statistic.

In my opinion, the best way to address the issue is to promote its education.

Making sure that all healthcare providers are aware of the scope of the problem and the responsibility they have to fight its spreading flames is a necessity. Integrating continuous teaching and identification of implicit bias in medicine is something that hospitals and programs could integrate into their curriculum for students and employees- in fact, some already do.

Healthcare workers should be required to undergo bias training routinely so that the importance of eliminating prejudice from medicine is constantly reiterated.

Aside from educating providers, there should also be an emphasis placed on making sure lower income communities are aware of how to go about planning for pregnancy. This includes making sure that they have better access to prenatal care, postpartum care, information about child-delivery methods, and options such as birthing centers and midwives.

This way, families can make educated decisions on how and where they want to have a child. Doing so can also increase patient self-advocacy, making their voices heard during interactions with medical staff and ensuring that they don’t feel coerced into making any decisions.

It is also crucial that such education is instilled in children from their teenage years itself so that they can grow up better informed and able to identify any issues that occur. Younger generations should be raised aware of the past so that they can learn from it.

Our outlook on issues that plague the community is a byproduct of information we receive, and when we receive it. Education and awareness are the two most powerful tools at our disposal when trying to resolve injustices that have gone on for ages.

The disproportionality of the African American maternal mortality rate in the United States is, as stated earlier, a persistent remnant of this country’s dark history.

The problem is widespread, rampant, and ongoing, but addressing it is the first step of many we must take so that we can create a world where a Black mother being able to see her child grow up is not a hope, but a guarantee.