It’s a tradition in my house, or really almost any Indian household, to drink tea or “chai” in the evening. The delicious brown liquid is typically accompanied by snacks such as Parle-G biscuits, spirals of murukku, or my personal favorite: tea rusk. Despite the countless scoldings I’d receive from my mother, I would always be found disobeying our set rule of two tea rusks per evening, stuffing my face with at least four before she could stop me.

As a child, my mother’s irritation was scarcely enough to stop me from devouring more of the breaded blisses than I cared to count, but as I grew older and more body conscious, this tendency of mine proved to be harmful to my body image. Although I had a bit of a pot belly as a kid- something my father would call a “backpack” instead of a six-pack (hilarious, right?)- an introduction to cardio and 10-minute ab videos helped burn most of the fat away. However, despite this fact, I still found my obliques to be carrying a bit of stubborn fat that seemingly refused to go away permanently. Daily side planks and Russian twists barely offered a solution, but I discovered that going a week without indulging in the tea rusk I once worshiped seemed to be a solution to this ongoing issue. However, it seemed as though if I gave into my cravings for just one day, I would usually see the effects in the mirror by the end of the week. Interestingly enough, the tendency to easily retain lower belly fat is not unheard of, and can also be connected to why Indians are up to six times more likely to have type 2 diabetes1.

Ironically, our problem with belly fat originates from India’s long history of malnutrition. In the hundred years it took for the British to occupy India and the additional hundred years the British ruled India- ending in 1947 with the country gaining its long overdue independence- twelve major famines occurred, killing an estimated eighty-five million Indians2,3. When famines are such a constant occurrence, the concept of “survival of the fittest” comes into play; in this case, those who can best combat malnutrition are defined as the “fittest”.

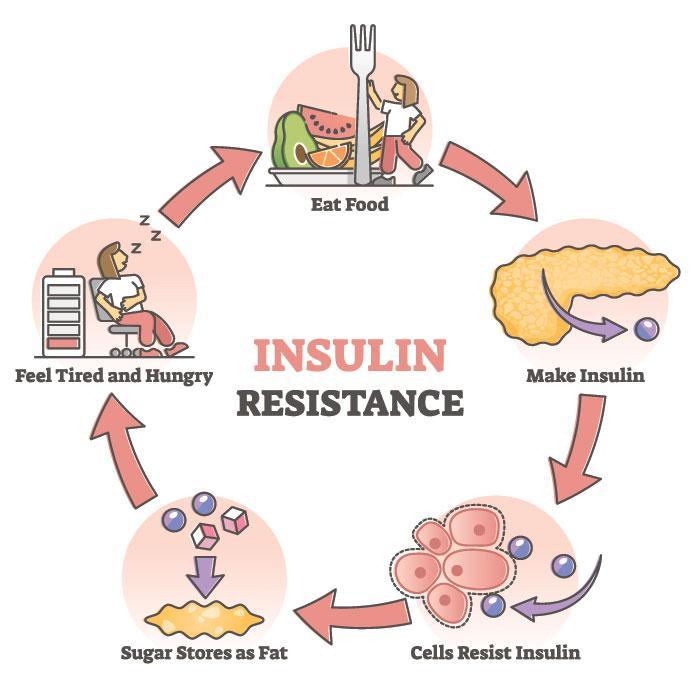

These recurring conditions prompted Indian bodies to adapt by lowering energy consumption, followed by a rapid deposition of energy as body fat which the body would burn for energy in the absence of glucose during famines6. Due to how their bodies were forced to burn fat as a means of energy, insulin- the hormone that allows glucose to enter cells- was used much less frequently than normal. Studies have shown that such a decrease in insulin action on glucose transport can lead to insulin resistance. This is further backed up by a research study conducted by Brown University which discovered that after surviving just one famine, the offspring of the survivors had a 2.02 times greater chance of having type-2 diabetes5,7. With this in mind, consider the effects that 12 major famines consecutively can have on multiple generations and their offspring. Now, consider the fact that the starvation-adapted bodies of Indian men and women do not fit into current times where food is not as scarce as it once was. Habits such as binge eating do not pair well with the way our ancestor’s bodies adapted, and we see this mismatch whenever we step on a weighing scale or put on a pair of jeans, only to realize that our waist has grown in circumference.

Although those famines took place centuries ago, it is important to realize the implications history can have on the present and future. Generational trauma is a pattern seen in many aspects of Indian culture, and in order to break the cycle, both an understanding of its origins and a plan to overcome the status quo are required.

First, let’s take a look at the science of type 2 diabetes. As mentioned earlier, insulin is a hormone that allows glucose to enter the cell; without it, glucose remains in the bloodstream waiting to be used. When there is an excessive amount of glucose in the bloodstream- a condition known as hyperglycemia- the pancreas secretes more insulin to compensate. Over time, this response becomes less effective and blood glucose levels continue to rise despite the pancreas releasing insulin due to a process known as insulin resistance.

So now that we know how type 2 diabetes occurs, let’s think about the ways we can prevent or even “reverse” it. One of the best ways this can be achieved is through resistance training, seeing as how studies have shown that doing so can result in a 16% increase in insulin sensitivity9. In addition, muscles are known to require more glucose than fat, tackling the problem of high blood glucose levels as well8. Keeping with the topic of exercise, it is also important to stay in an ideal body fat percentage, as obesity predisposes you to type 2 diabetes. Another such solution is learning how to deal with stress. When your body is under pressure, whether it be physical or mental, your adrenal glands release a hormone known as cortisol. Cortisol has been shown to increase blood glucose concentration as well as activate enzymes involved in the inhibition of glucose uptake10. In order to reduce cortisol levels, it is an absolute necessity to take up activities that allow your mind and body to destress. Meditation and going for walks outside are great ways to achieve this. It is also crucial to ensure that you are getting at least seven hours of sleep per night. A study performed on mice showed that six hours of sleep deprivation for just one night led to elevated glucose levels and fat content in the liver, as well as increased insulin resistance11.

The centuries of British rule India endured caused suffering that has bled into our very own genetics, creating problems for future generations if we are not wise in terms of our lifestyle. Overall, it is imperative that we depart from practices that are unhealthy for our bodies to ensure that the byproducts of our ancestors’ hardships will cease to affect us.

.Picture Credits

- British rule over India

- Chai and rusk

- Insulin resistance infographic