“My gut is telling me”, “I’m going to follow my gut”, “I shouldn’t have eaten that burrito last night”- these are just a few of the phrases you’ll hear me say when I’m in the middle of making a decision(or regretting one).

Listening to what our stomach is telling us- as strange as it may sound- is a pretty common occurrence whether we’re aware of it or not.

The reason behind this is largely due to the connection between your brain and your gut: a relationship that can control your physical health, mood, and even go as far as determining your chances of developing certain diseases.

Let’s first look at the basics: we eat food, it gets digested, and then whatever our body can’t use gets flushed- a process that seems rudimentary given how routine it is.

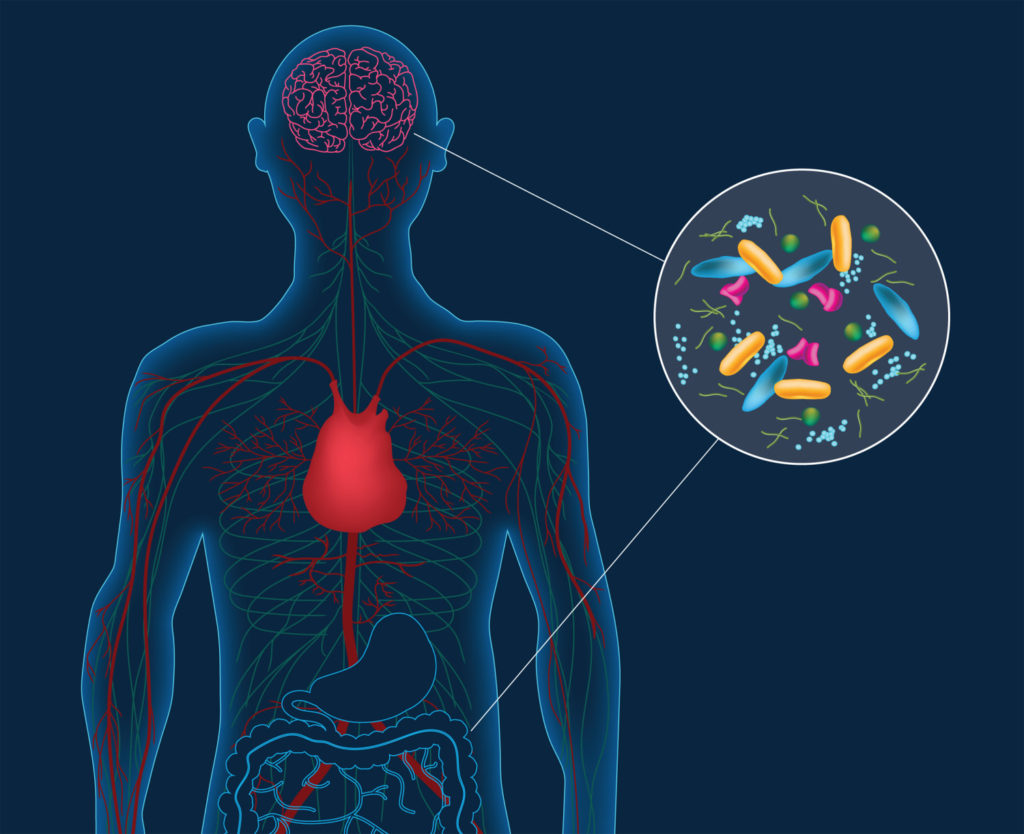

However, the process of digestion involves not only the organs of the digestive system that we’re used to hearing about (mouth, stomach, intestines, etc.) but also the trillions of microbes that make up what is known as our gut microbiome.

Our gut microbiome spans from our mouth all the way to our colon, but is most concentrated in the small and large intestines1. Essentially, it is a diverse ecosystem that performs a wide range of essential functions for our bodies. Certain bacteria in our gut can break down food that our body cannot digest, produce important nutrients, regulate our immune system, and even defend against certain pathogens2.

So how did we end up with this colony inside us, and where did it all begin?

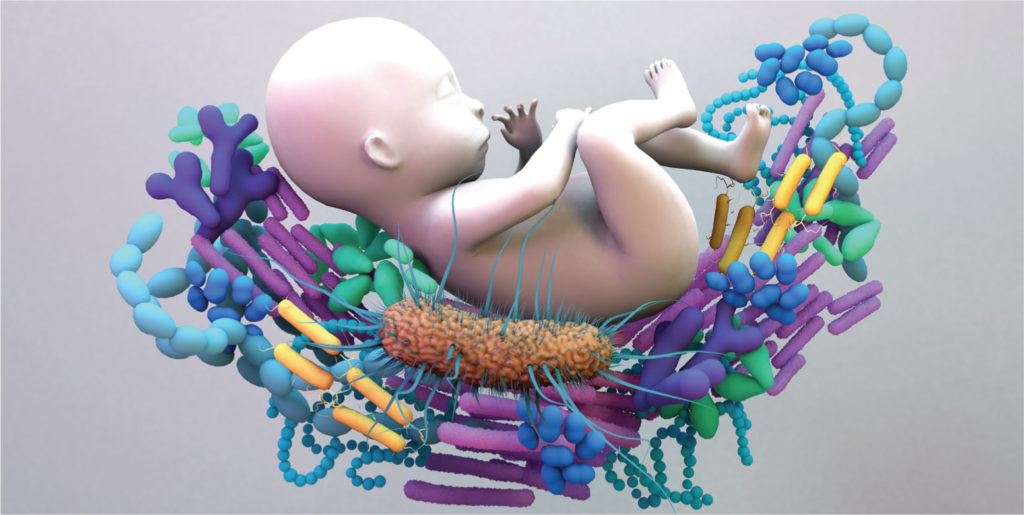

Well, bacteria are everywhere, and our bodies are no exception. When we are fetuses, however, we start off almost completely sterile in the womb. It is only when we pass through the birth canal that our bodies accumulate a microbiome that is passed down to us from the bacteria surrounding our mother’s skin and birth canal.

This invasion of microorganisms on our body during birth is welcomed by our body and is actually beneficial towards our health- in fact, infants delivered through C-sections do not receive the same kinds of bacteria as infants delivered through normal vaginal births and this plays a role in why they have an increased risk of developing chronic health conditions such as asthma, allergies, and type 1 diabetes to name a few3.

From the moment we are born, our microbiome begins to form until it becomes completely developed, which typically takes up to two years and sometimes more.

Breastfeeding contributes to this development, as breast milk contains compounds that nurture an infant’s beneficial gut bacteria and contributes to their healthy growth pattern4. Even after it becomes fully developed, our gut microbiome is still completely subject to change due to factors such as our genes, environment, use of medication, and diet.

For example, foods that are high in fiber promote good gut health because dietary fibers can only be broken down by microbiota that reside in the colon. This process releases compounds known as short-chain fatty acids(SCFAs) that limit the growth of certain harmful bacteria such as Clostridium difficile, stimulate immune cell activity, and regulate blood glucose and cholesterol levels5.

On the other hand, habits such as the excessive use of antibiotics can have an adverse effect on gut health, as they can inadvertently kill off beneficial bacteria and cause dysbiosis in the gut, allowing pathogenic bacteria to accumulate6.

Along with SCFAs, our gut microbiome is also responsible for synthesizing different vitamins, amino acids, and even neurotransmitters, which brings us back to the topic of how our gut is connected to our brain.

Our small intestine is responsible for most of the digestion that occurs in our body, and this is made possible by the fact that it contains enteroendocrine cells that assist in digestion by signaling the release of specific hormones7,8.

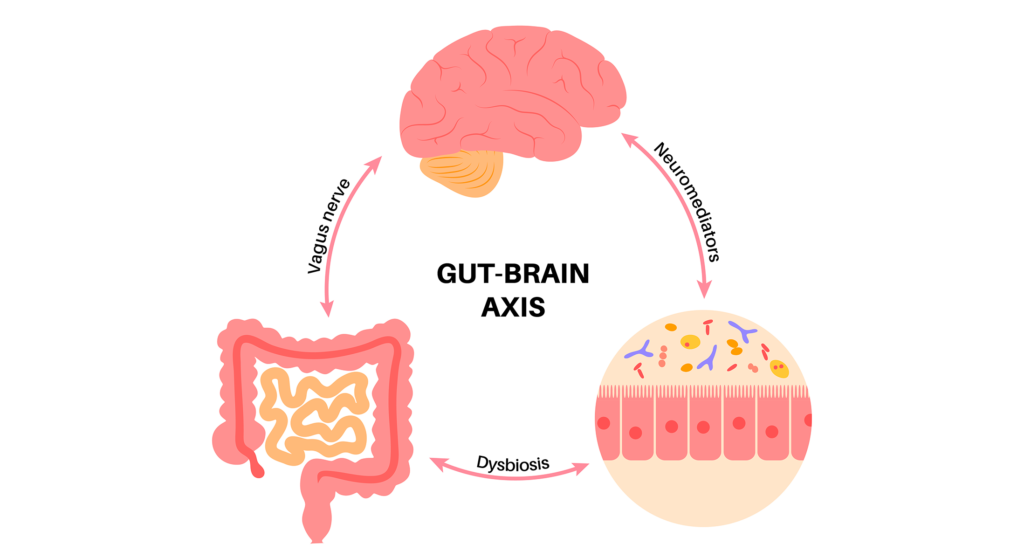

Some enteroendocrine cells known as neuropods synapse with a structure known as the vagus nerve; this forms the pathway of the “gut-brain axis”(GBA) that links the “emotional and cognitive centers of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions”, allowing for two-way communication that enables the state of our gut to impact our brain, and vice versa9.

The incredible role this connection plays in our body is emphasized by the fact that our digestive system is responsible for supplying our body essential compounds.

Our microbiome contributes significantly to this supply, as shown by a study where the enterochromaffin cells in germ-free mice “produced approximately 60 percent less serotonin” than mice that had normal bacterial colonies. This serotonin deficiency was reversed in the germ-free mice when their guts were recolonized with normal microbiomes10. Other neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine are also shown to be synthesized with the help of our gut bacteria, and along with serotonin, they are sent to the brain via the vagus nerve.

It goes without saying that if the production of such compounds were to cease, both our physical and mental health would deteriorate.

An interesting study showed that bacteria-free rats that received a fecal transplant from humans diagnosed with major depression began showing signs of anxiousness along with disinterest in pleasurable activities due to changes in their metabolism of tryptophan- an amino acid used to produce serotonin- further signifying the connection between our gut and brain11.

Apart from having an effect on our mental health, the state and development of our microbiome can also indicate our risk of acquiring neurodegenerative diseases.

Even before traditional symptoms of Parkinson’s disease such as tremors, bradykinesia, and rigid muscles appear, those affected by it have been shown to experience changes and problems in their gastrointestinal tract12.

Studies have shown that Parkinson’s patients have gut microbiomes that differ significantly from those of control groups, and these alterations may cause the accumulation of a protein known as alpha-synuclein in the intestine which then gets transported to the central nervous system through the vagus nerve14,15.

Increased alpha-synuclein expression in the brain has been shown to adversely affect the firing activity of dopamine neurons, contributing to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s13.

Furthermore, research has also identified differences in the microbiota of Alzheimer’s patients and control groups, along with correlations between types of bacteria found in their stool and the amount of Alzheimer’s related plaques and tangles in their brain16.

If you haven’t had enough of me beating a dead horse yet, let me say it again: your gut health is important!!

While further research is required to get more information on how specific microbes or their by-products promote the progression of related disorders, the role our microbiome plays in maintaining homeostasis is undeniable.

Maintaining good gut health can come in many forms, the first and foremost is having a diet that promotes microbe diversity and richness.

Foods known as probiotics achieve this by introducing beneficial bacteria into our gut, whereas prebiotic foods contain fiber that acts as food and fuel for those good bacteria.

As mentioned earlier, cutting down on antibiotics use when not necessary is also important because not only do they kill our beneficial bacteria, but it also takes months to restore gut microbe diversity and balance; in many cases, it’s not even possible to restore our gut to its pre-antibiotic state17. Avoiding stress is also important as high cortisol levels have been shown to cause dysbiosis.

While it may be hard to wrap your head around how the state of our gut can influence so much in our body, I hope I’ve helped you come to appreciate our microbiome and become more mindful in taking care of it.

More often than not, the way our stomach feels is an indication of how well it’s functioning and how healthy we are, and improper health can change the way we feel and function.

From childhood, we’re taught that we should be wary of what we put inside ourselves, and this is all the more important when considering our coexistence with the trillions of microbes within us.

So the next time you get that strange feeling in your stomach, or the unpleasantly familiar one that comes shortly after eating your chicken 65, just know that your microbiome is hard at work.