As someone who has only learned about the Holocaust through textbooks, documentaries, and pictures of a guy with a funny-looking mustache, it’s hard for me to grasp the sheer fear and turmoil felt during the Second World War. However, despite the years that have passed since those hostile times we are all still witnesses to the aftermath of the bloodshed.

I’ve always found it ironic how many of the tactics, technologies, and treatments developed for war later end up leading to discoveries or achievements that help humanity progress as a whole. For example, we have the American civil war to thank for propelling anesthesia from a relatively new discovery to a now imperative part of surgeries. Decades later, World War I bought the regular use of blood transfusions, which, at the time, was a rare procedure. So what did World War II give humanity? While the widespread use of antibiotics seen during the war might’ve been the crowning achievement of science back then, I believe that the Nuremberg code is what defines medicine and research as we know it today.

The Holocaust is known for the genocide of European Jews performed by Nazi Germany between 1941 and 1945. This mass murder was designed to promote the Nazi ideology of eliminating unfavorable genes from the societal gene pool in order to create the perfect race- a concept known as eugenics. The Germans would set up concentration camps and have prisoners perform laborious activities, all while living under ghastly conditions and receiving little to no nutrition. Eventually, the prisoners would be sent to gas chambers where they would be killed in groups. At least, that was how most of them died. In some camps, the prisoners would be used by physicians as test subjects for heinous experiments conducted against their will.

In the case of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, physicians sought to determine if sulfanilamides were an effective treatment for gas gangrene- a condition that caused a heavy toll on the German army in the previous World War3. In order to replicate the conditions the soldiers faced on the battlefield, physicians would make incisions into the prisoners’ legs and would add wood shavings, cloth fibers, dirt, and glass fragments along with strains of bacteria in the wound- all while they were conscious. Some prisoners were given sulfanilamide treatments while some received no treatment at all, but regardless of whether or not they received any form of medication all the subjects developed life-threatening infections and abscesses. It was determined that the sulfanilamide treatments had no effect, but what is truly outrageous is the fact that this was already known to German scientists.

One of the head physicians involved in the experimentation, Karl Gebhardt, was well aware of German, American, and British studies regarding sulfanilamide’s ineffectiveness in treating gas gangrene. However, Gebhardt conducted experiments he knew were unnecessary in order to defend his own approach to the surgical management of contaminated wounds, and his belief that sulfanilamides did not change the course or mortality rate of gas gangrene. Futile experiments such as these on unwilling prisoners resulted in virtually no medical advancement, the deaths of over twenty-eight thousand in that camp alone, and left the survivors permanently physically and psychologically handicapped.

This was mostly due to how the physicians who were most willing to conduct human experimentation were usually the ones who were most careless, as well as ones who were not able to find reputable work anywhere else. In addition, the nature of the test subjects also tended to skew the data as malnourished and fatigued prisoners do not represent the general public.

Certain experiments, however, were able to gain some useful knowledge. For example, in the Dachau concentration camp, Dr. Sigmund Rascher would drop inmates into freezing water in order to test survival gear for the Luftwaffe. These trials provide some of the most comprehensive data describing end-stage hypothermia in humans2. Even to this day, there is no way to determine the accuracy of Rascher’s results seeing as how replicating his methods would be a violation of the Nuremberg code.

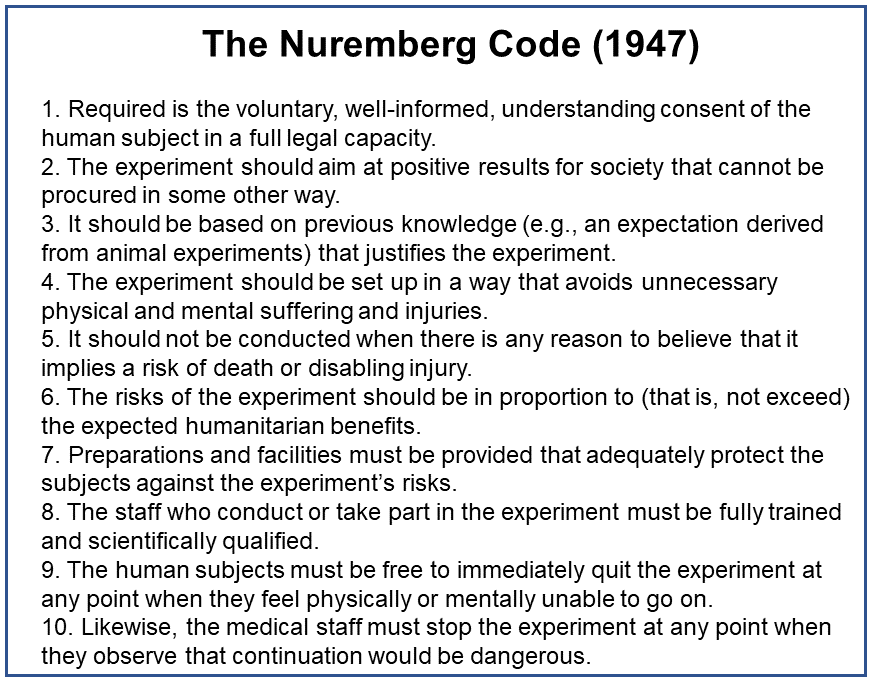

The Nuremberg Code is a set of research ethics regarding human experimentation issued by judges at the Nuremberg Doctor’s Trial where twenty-three leading German physicians and administrators for their willing participation in the execution of the Holocaust. The Nuremberg Code consists of the following ten principles1:

While the Hippocratic oath was also designed to ensure patient safety, it focuses more on what the physician should and shouldn’t do. On the other hand, the Nuremberg Code outlines the rights of the patient when being subject to experimentation. Its creation went on to inspire The Declarations of Geneva and Helsinki as well as the Beecher Paper which are also considered to be instrumental in the implementation of laws concerning human experimentation4.

The Nuremberg Code’s emphasis on the concept of “informed consent” in regard to the patient, and its global influence on human rights in medicine is why it is now considered to be one of the most important documents in the history of clinical research ethics- ensuring that patients such as the prisoners of the Holocaust will never be abused by physicians under such circumstances ever again.

Throughout the numerous horrific experiments German physicians conducted on concentration camp inmates, the significant number of deaths resulting and the largely insignificant results derived from them sadly reflect the importance of the Nuremberg code. Although such human testing gave very little advancement to medical knowledge, the resulting development in bioethics is the best we have been able to make out of what was truly a terrible situation.